Back of the Napkin #4: The Perfect Investment

On avoiding talking to anyone

Back of the Napkin is an ongoing series by Brian Shih and Sebastian Park featuring a line-by-line deep dive of this interview with Jeremy Giffon on the Invest Like The Best podcast. You can find all previous posts in the series here.

Follow along here on Substack, or Seb’s LinkedIn. If you have any suggestions, comments, or want to join in as a collaborator on a particular topic, please reach out! You can reach Brian on Twitter and Sebastian on Twitter and TikTok.

Back of the Napkin #4: The Perfect Investment

Finally! On to the next topic:

Patrick: So there's 1 million people that are incredibly smart from Buffett on down about the qualities of a business or the qualities even of a founder or a legal structure around something, I think you uniquely come at investing very often from the meta circumstances of the situation surrounding the asset and the deal, and the incentive structures for all the stakeholders in the deal. And so with that lens, I'd love you to describe your perfect investment, if you will.

Jeremy: [00:04:42] I don't know if it's reachable, but to me, the perfect investment would be one where you actually never have to talk to any of the people or know anything about the business. You can just understand the circumstances around it and the incentives of the various interested parties and feel out why this opportunity exists, why you can solve it, and then why you're getting paid for it without ever knowing anyone. I think a lot of these, especially in the private markets, are just coordination problems. You're basically coming in, into a log jam and just unjamming it and you can get paid for that unjamming.

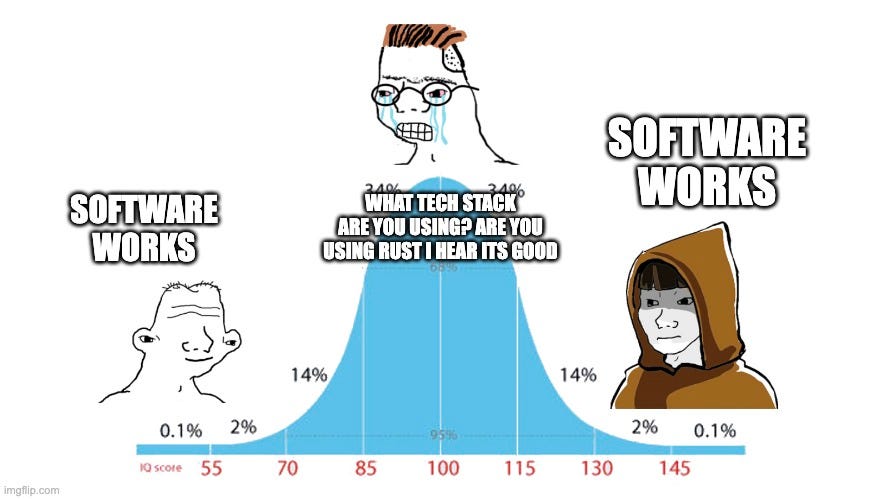

When it comes to buying software businesses, it's amazing how many people would ask me about technical due diligence. And it never crossed my mind. If this is a business that people are paying millions of dollars for, it clearly works, the software works, what do you need to due diligence? Obviously, it's different in a hard tech company or something. But even then, if it works, it works.

There’s a distinction being drawn here between a perfect business and perfect investment. It is telling that Giffon’s perfect business (the merchant banks discussed previously) isn’t mentioned as a perfect investment, and in fact it seems like Giffon’s answer here is less about the kind of investment, and more about how easy it is to evaluate the prospective investment.

Giffon is essentially saying that the perfect investment is one where the structural incentives and circumstances surrounding the deal make it obvious why the opportunity exists and you can make money from it. This stems from his background in investing in “special situations in private markets” (the namesake of the podcast episode) — more on that later.

In other words he’s looking for investments where it’s obvious what value he is adding as an investor (a negative example of this is buying public equities — what value do you add?), and where it’s super clear who stands to benefit from the situation, all without talking to anyone.

Why does he care so much about not talking to anyone? He never says directly, but we suspect it’s a combination of 1) time leverage, and 2) avoiding bias.

Usually talking to people takes time – coordination problems aside, travel in order to diligence in person, and context switching costs are all real. If you can bypass this and are capable of looking at the reality of a situation and figure it out yourself, this is time leverage (and we know how much Giffon loves leverage).

The second issue with talking to people (we know this makes us sound like misanthropes!) is if they’re pitching you on an investment, they’re fundamentally biased towards getting you to invest. It’s especially bad if it’s the business owners doing the pitching — they know more than you, and have every incentive to sell you a bill of goods. So all else being equal, if you can figure it out from first principles without talking to people, you can avoid the problem of adverse selection.

The example he gives here is around technical due diligence: Suppose you are investing in a software company that exists and has millions of paying customers. How much technical diligence do you need to do? On the one hand, it’s probably prudent to make sure the thing isn’t built out of duct tape and baling wire. On the other hand… it works? The product-market fit speaks for itself.

That said, it’s not clear this approach works for all kinds of investments. It assumes a business already exists, that you can observe the demand for the product, and that it works; this makes sense given Giffon’s history at Tiny where they bought and rolled up a bunch of existing internet software businesses. But this simply isn’t possible for certain kinds of investments like early stage startup investing, where the product just doesn’t exist yet. What else can you do but talk to the founders?

In that case, your own technical understanding as an investor might matter more. Having a strong grasp of AI and machine learning should count for something when evaluating one AI startup vs another, even if the technical details are only part of the story.1

Giffon sort of glosses over all of this, maybe because it’s personal preference: he really would rather invest in something that is obviously working and requires no talking with anybody to diligence. But how much of that is bias from his background at Tiny vs what actually makes the “perfect” investment?2

It’s clear there are inefficiencies in markets, especially in the opaque world of private companies, which is what Giffon and Tiny specialized in. As a result, some strategies for exploiting these inefficiencies should exist, and maybe what Giffon is really getting at is that they’ve found something that works for them.

But in the end, it’s impossible to quantify what makes one investment the “best”. Is it risk-adjusted returns? Returns vs time spent talking to people? There are endless metrics one could optimize for. Maybe Giffon just truly hates talking to people (doubtful for a guy giving a 1.5 hour podcast interview). All we can really conclude is that this kind of investment might be perfect for Giffon, and not much more than that.

But hey, as he says himself, if it works it works.3

One fun example: There once was a streaming website that pitched the idea of lagless streaming. This happens to violate the fundamental limits of the speed of light. However, they were able to receive a good amount of investment, and exit as a function of traction from content creators who wanted no-latency streaming, when in reality the lower latency was just a function of fewer people watching the content.

It’s hard to tell exactly how effective Tiny’s strategy is — clearly they were successful enough to survive for fifteen years and IPO on the TSX Venture Exchange earlier this year via an amalgamation with WeCommerce, a company that Tiny itself funded and launched. The stock is down roughly 30% since then, but the founders are certainly doing just fine.

Until it doesn’t.